An increasing proportion of women reaching their 30s, are doing so childless. I agree with demographers and commentators that this is the critical factor in our declining fertility rate but contend that we cannot / should not discuss these falling birth rates without signposting the impact of abortion.

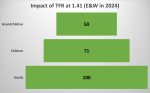

In August 2025, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that in 2024, the total fertility rate (TFR) in England and Wales was 1.41 children per woman, the lowest value on record.[1] Replacement-level fertility requires a TFR of 2.1, which will ensure a level population number, assuming no change in mortality rates and discounting net migration. Ours is now one-third below replacement which, if it continues, will have a very significant demographic impact in coming generations: 100 young adults today will have 71 children and they will have 50 children.

Each year the ONS also reports data and analysis related to the completed family size for all women sharing the same birth year (a cohort); in April of this year it published data for 2023.[2] The following graph shows the number of children for women reaching 45yo, grouped together into seven different cohorts based upon their year of birth. Women born in 1978 are the last cohort to reach age 45 by 2023.

Demographers will often point at the predominance of women with two children, noting that even as TFR declines, the two-child family remains. Some, such as Stephen J Shaw, lean into the change in the proportion of women who, on reaching 45yo, remain childless. It is worth looking more closely at these data and, as we do so, noting that the 1950 cohort is the first of these to have easy access to contraception and abortion during their reproductive years, 15-45.

| Year of birth of woman | Average family size | Percentage – no live born children |

| 1920 | 2.00 | 20.9 |

| 1930 | 2.35 | 13.4 |

| 1940 | 2.36 | 11.2 |

| 1950 | 2.07 | 13.6 |

| 1960 | 1.98 | 19.0 |

| 1970 | 1.91 | 17.3 |

| 1978 | 1.95 | 16.4 |

To be fair to Shaw, there has been an increase in the percentage childless since the low of 11.2 in 1940, but no significant change in more recent cohorts.

However, in the same dataset we find a significant increase in the proportion of women remaining childless when reaching age 30yo.

As he outlined in a recent article in The Times, Shaw points to this as the most significant driver behind our falling fertility rate, he says that whilst parents are having roughly the same number of kids as in the 1970s, two children or more, it is the growing proportion of women remaining childless that is causing the decline in overall TFR.[3]

In August 2025, Shaw published his proposed microdemographic framework, which he suggests will be helpful to those challenged with setting policies to mitigate the impact of declining birth rates. This framework would report not just TFR but two new measures, the Total Maternal Rate (TMR) and Children per Mother (CPM); TFR = TMR x CPM.[4]

This makes a lot of sense, as can be seen when reviewing Shaw’s data for the UK in 2020. His framework shows that whilst the TFR was 1.57, 70% of women had become mothers with an average of 2.23 children each. This would seem to indicate that the reason TFR is below the required replacement level, is because 30% of women remained childless.

In The Times, Shaw outlines how, even though women want to have children, many in their twenties are now postponing parenthood:

“There’s a popular belief that parenthood is something you can safely postpone. That you can get education, career, travel, stability sorted — and then start a family. But here’s the sobering truth: in the UK, from ONS data on births by age, a woman who reached the age of 28 without children in 2023 had only a 50 per cent chance of ever becoming a mother. Before 28 most women who want children are still likely to have them; after 28 the odds flip from “more likely” to “less likely”.

Shaw, and others such as Miriam Cates commenting on his research,[5] think this is where our focus needs to be, on helping these young women to overcome whatever it is that is ‘getting in the way of parenthood’, what is driving their ‘postponing of parenthood’ and ‘unplanned childlessness’. I tend to agree but I contend that we cannot do so without being willing to at least consider the impact of abortion.

In July 2025, the ONS released its latest set of data related to Conceptions in England and Wales.[6] From these data we can find how many women aged up 29yo become pregnant each year and from these conceptions, how many result in births and in abortions.

| Year | Conception rate per 1,000 women | Maternity rate per 1,000 women | Abortion rate per 1,000 women | Conceptions ending in abortion |

| 2012 | 83 | 62 | 21 | 25% |

| 2017 | 73 | 53 | 20 | 28% |

| 2022 | 67 | 43 | 24 | 36% |

These data show a reducing proportion of young women becoming pregnant but amongst those who do, an increasing use of abortion. My analysis of these data over the ten years to 2022, shows that more than 40% of those young women who remain childless when reaching 29yo would not have been so without abortion. It is not unplanned childlessness, for these women it is a decision upon becoming pregnant, not to continue into motherhood at that time, for a whole myriad of reasons.

I contend that a rate of 36% of conceptions ending in abortion is very significant and we must have this on the table when discussing the decline in motherhood for those reaching their thirties. The same dataset shows for those aged up to 25 in 2022, 48% of conceptions end in abortion; this is consistent with my earlier estimate that “Half of all Generation Z Pregnancies now end in Abortion.”[7]

Shaw’s research suggests that about 50% of these childless thirty-year-olds will never become mothers, even though most of them want to. There is a heartrending sadness in this and I wonder if abortion providers ever mention this risk to the young women considering terminating what might turn out to be their last chance at motherhood.

[1] Population Health Monitoring Group. (2025, August 26). Births in England and Wales – Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/birthsummarytablesenglandandwales/2024refreshedpopulations

[2] Childbearing for women born in different years – Office for National Statistics. (2025, April 2). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/conceptionandfertilityrates/datasets/childbearingforwomenbornindifferentyearsreferencetable

[3] Shaw, S. J. (2025, August 30). Our baby crisis is down to bad timing, not biology. The Times. https://www.thetimes.com/comment/columnists/article/baby-crisis-biology-fertility-b5lg7f8s7

[4] Shaw, S. J. (2025). On a microdemographic framework for decomposing contemporary fertility dynamics. Scientific Reports, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11522-9

[5] Cates, M. (2025, August 27). The celebration of childlessness has gone too far. Yahoo News. https://www.yahoo.com/news/articles/celebration-childlessness-gone-too-far-161359832.html

[6] Conceptions in England and Wales – Office for National Statistics. (2025, July 9). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/conceptionandfertilityrates/datasets/conceptionstatisticsenglandandwalesreferencetables

[7] Duffy, K. (2023, November 27). Half of all Generation Z Pregnancies now end in Abortion. Percuity. https://percuity.blog/2023/09/12/half-of-all-generation-z-pregnancies-now-end-in-abortion/

Discover more from Percuity

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great stuff Kevin – lucid and compelling. How tragic!

Mark

Sent from Outlook for iOShttps://aka.ms/o0ukef

LikeLike

Thanks Doc. I think we need to consider if this significant risk of childlessness should be included in abortion consent.

LikeLike