The numbers from the Office for National Statistics could not be clearer: England and Wales are falling short of replacement-level births, with maternities sliding year after year while abortions climb to nearly a third of all conceptions. On paper, the “missing” births are more than accounted for by abortions—but the idea that banning abortion could reverse the trend is a political and practical non‑starter. The real challenge is not simply economic incentives or legal restrictions, but the deeper question of why fewer young people want to start families at all.

Office for National Statistics

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) publishes a dataset, Conceptions in England and Wales, in which it details numbers and rates of conceptions, maternities, and abortions.[i] [ii] This is important because it is the ONS that has determined that these data can be combined and compared, we do not need to bring in abortion data from other sources, there is no need for Freedom of Information requests or extrapolation or potentially biased interpretation of other data.

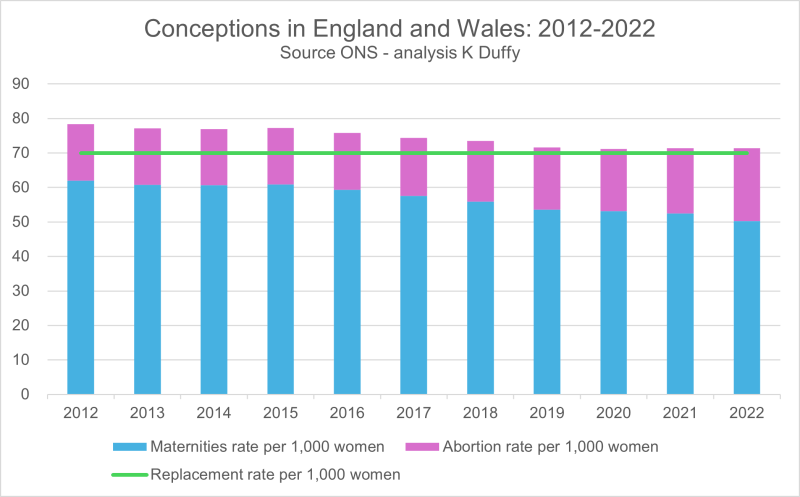

The ONS defines replacement level fertility as the average number of children a woman needs to have to ensure population stability in the absence of migration. This is typically set at 2.1 children per woman, which is equivalent to 70 children born each year for every 1,000 women of reproductive age, those from age 15 to 45.[iii]

The ONS dataset provides the rates per 1,000 women in each year. To maintain a stable population total, we need 70 maternities per 1,000 women each year. This graph shows the annual rates for maternities and abortions and indicates the replacement level of 70. As shown, the maternities rate has been below replacement level in each of these years, with a notable decline in recent years. The Office for National Statistics shows in these data, that when added together, maternities and abortions would have totalled more than the required replacement level.

In the years from 2012 to 2022, in England and Wales, the ONS reports a total of 9.3 million conceptions, 7.1 million maternities, and 2.2 million abortions. To maintain the replacement level, we needed 8.7 million maternities, the 1.6 million shortfall in births being significantly less than the total abortions.

These data show a total fertility rate of 1.9 children per woman in 2012, falling to 1.5 in 2022, a decline of 19%. The underlying trends show a decline in both the annual totals and the rates of conceptions and maternities, whilst each year the total number of abortions and rate of abortions per 1,000 women continue to increase.

Office for Budget Responsibility

In July 2025, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) warned that if birth rates remain low and migration does not stay high, the UK will face a growing imbalance between the number of older people and the working-age population. This shift will increase pressure on public finances, making it more difficult to sustain services such as pensions, healthcare, and social support.[iv] These concerns were further exasperated in August when the ONS published a TFR of just 1.41 in 2024, noting that this “represents the lowest value on record for the 3rd year in a row.” [v] It seems clear to all who look at the data, that without a reversal in birth rate trends or sustained migration, the UK faces rising dependency ratios and fiscal pressure from ageing populations.

What if we ban abortion?

But isn’t the answer obvious? Surely we can learn from what has been happening in the past, it is clear that abortion has been a very significant driver of our falling birth rates. In 2022, almost 30% of all conceptions ended in abortion.

It is a fact that in the past there were more abortions than the gap in required births. It is plausible that if nothing else changes, this could well be a trend that continues into future years. However, we cannot state with any certainty that if abortion was not so easily accessible, then we would not have this birth rate crisis.

Let’s say that we could change the law to ban elective abortions, which total 98% of all abortions, so still allowing some for medical indications,[vi] wouldn’t this lead to an increase in the birth rate? Academics don’t think so, most are inclined to suggest that any increase would be small, perhaps just 5% compared to the 30% downward impact noted above, but, that said, there are no substantive studies that can rightly be applied to an imagined future E&W in which abortion was legally restricted.

Increased use of contraception

There is little doubt that if abortion was not permitted and no longer accessible on-demand from the NHS, many couples would change their behaviours to avoid an unwanted pregnancy. We know that elective abortions are for those pregnancies that are unplanned, unintended, and unwanted, so it is somewhat surprising that BPAS reported that in 2023, 69.6% of women presenting for an abortion were not using contraception at the time of becoming pregnant; these women instead decided to use abortion as their birth control.[vii] The remaining 30% of women attending BPAS, were there because they had been using an ineffective method of contraception, one that had failed.

It is very likely that if abortion was not permitted, there would be a subsequent increase in the demand for and use of effective long-acting or permanent methods of contraception and further moves to make emergency contraception available over-the-counter. It is also plausible that some women would access abortion pills online, and that such supply would be made easy by activists as e.g., we see happening across the U.S., pills being posted into states with abortion restrictions, or into Poland and Malta. Activists would step up their encouragement to women to have abortion pills in their bathroom cabinets, ready to be used when experiencing a late or missed period, without first confirming pregnancy.

Government responses

The uncomfortable reality is that, no matter the economic and social pressures forecast by the OBR and others, neither this parliament nor the next is likely to pursue abortion bans. The political fallout from being branded “forced‑birthers” is perhaps even more toxic than grappling with immigration or the spiralling costs of pensions and social care.

High housing costs, childcare shortages, and the relentless squeeze of living expenses are the barriers most often cited by young people delaying or avoiding parenthood. Ministers speak of removing these obstacles so that those who choose to have children can do so—but that conditional, “if they so choose,” is at the heart of the problem. The concern is not only affordability, but desire: what if fewer young people actually want to start families, regardless of incentives?

Governments worldwide have tried to shift this trend. France, Hungary, Poland, Singapore, South Korea, and Australia have all introduced fiscal incentives—cash bonuses, tax breaks, childcare subsidies—to encourage higher birth rates. These measures can deliver short‑term bumps, but rarely alter the long‑term trajectory. Where there has been more success, as in France, it has come from pairing financial support with structural reforms that make raising children compatible with modern work and lifestyles. Without tackling those broader issues, money alone does little to change fertility trends.

The real challenge, then, is not just enabling choice but reshaping desire: how to inspire, support, and gently nudge more young couples towards wanting—and embracing—parenthood.

[i] Population Health Monitoring Group. (2025, July 8). Conceptions in England and Wales – Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/conceptionandfertilityrates/bulletins/conceptionstatistics/2022

[ii] The ONS defines each of these as follows: Births include live births and stillbirths, unless otherwise stated; Conception is a pregnancy that leads either to a maternity or a legal abortion. We do not hold data on pregnancies that lead to miscarriage or pregnancies ending in illegal abortions; Maternity refers to a pregnancy resulting in the birth of one or more live-born or stillborn children. The number of maternities represents the number of women giving birth rather than the number of babies born (live-born and stillborn).

[iii] (70/1,000)*30 = 2.1 or (2.1/30)*1,000 = 70

[iv] Office for Budget Responsibility. (2025, September 16). Fiscal risks and sustainability – July 2025 – Office for Budget Responsibility. https://obr.uk/frs/fiscal-risks-and-sustainability-july-2025/

[v] Population Health Monitoring Group. (2025, August 26). Births in England and Wales – Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/birthsummarytablesenglandandwales/2024refreshedpopulations

[vi] The author supports such abortion restrictions as a moral and social good but does not consider this plausible in the foreseeable future.

[vii] McNee, R., McCulloch, H., Lohr, P. A., & Glasier, A. (2025). Self-reported contraceptive method use at conception among patients presenting for abortion in England: a cross-sectional analysis comparing 2018 and 2023. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health, 51(3), 186–190. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2024-202573

Discover more from Percuity

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[like] Mark Pickering reacted to your message:

LikeLike